“Older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend.” These words by Mark Twain echo the timelessness of Varanasi — a city that has not only survived but thrived across millennia, embracing contradictions and diversity as a way of life. This city is not just a dot on a map; it is a living, breathing organism—overflowing with devotion, music, mysticism, and resistance.

The Ancient Roots: Kashi and the Buddha

Archaeological evidence reveals that northern Varanasi has been inhabited since at least the 9th century BCE. Known then as Kashi, it was one of the 16 mahajanapadas of ancient North India. By the time of the Buddha, it had already blossomed into a center of learning and spiritual discourse.

It was here, in nearby Sarnath, that the Buddha delivered his first sermon after enlightenment, introducing the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. He emphasized human equality, compassion, and reason—values that challenged rigid social hierarchies and laid the foundation for Buddhism.

Syncretic Spirituality and Bhakti Movement

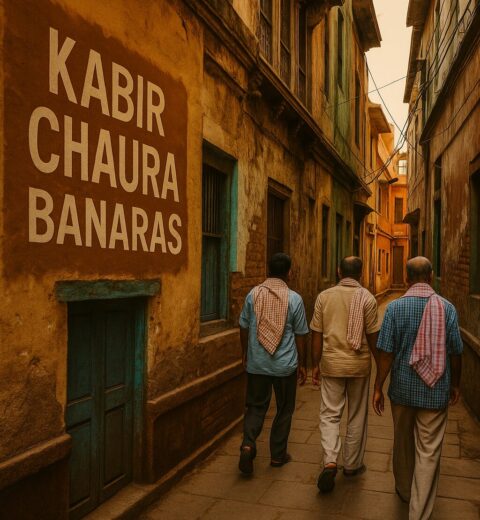

Despite being a Hindu stronghold, Varanasi has always encouraged spiritual experimentation. The Bhakti movement emerged from this soil, led by poets and saints like Kabir, Ravidas, Tulsidas, and Ramananda. They denounced casteism and religious orthodoxy, advocating love and equality over ritual and priesthood. Their teachings later influenced Guru Nanak and became central to Sikhism.

Kabir, in particular, became the conscience of Banaras—mocking mullahs and pundits alike with sharp irony. His verses still resonate in the gallis of the city.

A Melting Pot of Religions

Varanasi’s pluralism is evident in its shrines to both major deities and obscure folk gods. From tantric worship of Kal Bhairav to the boatmen’s prayers to Nishad Raj, spirituality here defies easy classification.

About 30% of Varanasi’s population today is Muslim, many of them weavers carrying forward a rich tradition of textile artistry. Hindus visit Sufi shrines, while Muslims visit Aghori babas. This intermingling of traditions is locally celebrated as Ganga-Jamuni Tehzeeb—a cultural confluence that finds its roots in the city’s very soul.

The Mughal Influence: Oppression or Opportunity?

The Mughal period is often portrayed in black and white. While temple desecrations under rulers like Aurangzeb were politically motivated, the period also saw a flowering of Hindu devotional literature, arts, and public infrastructure. Akbar’s ministers patronized temples; Ahilyabai Holkar later rebuilt the destroyed Vishwanath Temple.

The Bhakti wave reached its zenith during Mughal rule, with Tulsidas writing the Ramcharitmanas in Avadhi—a text that transformed Rama into a pan-Indian deity and birthed traditions like Ram Leela.

Cultural and Linguistic Evolution

Modern Hindi emerged in Varanasi, crafted as a language of nationalist identity by blending Sanskrit with local dialects and removing Persian influence from Hindustani. Yet, this anti-syncretic linguistic reform paralleled the rise of both Hindu and Muslim revivalist ideologies in the colonial era.

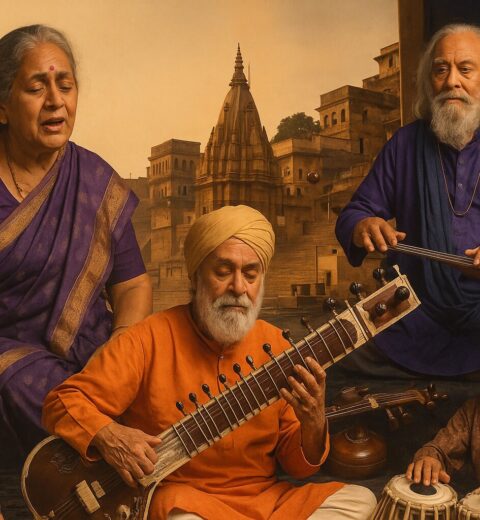

Still, the Indo-Persian legacy survives in art, clothing, architecture, and especially music. The city gave us legends like Ravi Shankar, Bismillah Khan, and Girija Devi, whose gharanas continue to echo along the ghats.

Death, Moksha, and Mythology

Manikarnika and Harishchandra Ghats are not just cremation sites—they are symbols of spiritual passage. Hindu belief holds that dying in Varanasi ensures instant Moksha, liberation from the cycle of birth and death. Shiva himself is said to whisper the Tarak Mantra into the ears of the dying.

Yet this idea has faced critique—from Kabir to modern theologians—for bypassing karmic law and reinforcing caste-driven rituals around death.

Challenges of the Present

In recent decades, the rise of Hindu nationalism has begun to erode the pluralistic fabric of Varanasi. Once a city of tolerant coexistence, it now stands at the edge of spiritual and political polarization. The story of Varanasi is no longer just about myths and rituals; it is also a tale of resistance against historical distortion and cultural homogenization.

Conclusion: Preserving the Soul of Banaras

Varanasi’s greatness lies not just in its age or its spiritual fame, but in its ability to absorb and reflect a thousand currents of human experience. From the chants of Buddhist monks to the verses of Kabir, from Mughal patronage to folk rituals, Varanasi is India in miniature—complex, contradictory, and endlessly alive.

To understand Banaras is to understand India itself. And to preserve Banaras is to protect the pluralism that is the bedrock of Indian civilization.